Artist Conversations, Vol. 4

- Zach Harney

- Sep 18, 2025

- 16 min read

Greg Manchess

Few artists capture the sweep of imagination and the intimacy of human expression quite like Greg Manchess. Over his 50 year career, his work has graced everything from National Geographic and The Smithsonian to bestselling novels and cinematic posters. In addition to his commercial work, he’s celebrated for Above the Timberline, a fully illustrated novel that blends narrative and fine art in groundbreaking ways. In this conversation, we delve into the long and winding path that led him to where he is today, his creative process, and his more recent interactions with the small and fine press communities. We are so excited to finally share this conversation with one of our favorite illustrators and hope you enjoy it as well!

Q: You have been a working illustrator for almost 50 years now and the scope of your work is extremely diverse. Can you tell us a little bit about how your journey as an artist began from an early age? Were there any defining moments that shaped your path?

It's actually over 50 years, if you count my years in school. I went to art school thinking that I would get taught how to paint and draw. That makes sense, right? An 18-year-old says, “I'll go to art school, and they'll teach me what to do," but they didn't. What actually happened is I graduated four years later, scratching my head thinking, “I guess I'm going to go look for gallery jobs myself.”

A friend of mine had gotten an art director's job at Better Homes and Gardens in Des Moines, Iowa. She told me that she was working with this place called Hellman Design, and I should check them out. They're a studio in Waterloo, Iowa. So, I went down there, walked in the door, and they had a show on the wall of the six artists that were there. I fell in love with their work right away. It was professional, the kind of drawing I wanted to do, and immediately hoped that they would hire me.

I showed them my portfolio, and I got hired based on my drawing ability, not my finished work, because it was all over the place. I had a lot of pencil and charcoal sketches, pieces from my figure drawing classes. They saw that, and that sold them, because they figured I knew how to draw. At that point, I really didn’t know how to paint yet. They kept pushing me away from paint in art school. They said, “Don't oil paint, because it's dead.” Despite that, I tried anyway on my own, and I got into it. Hellman hired me, but I was the low man on the totem pole, and I had to work hard to live up to what the guys around me could do.

My early pieces were just horrible. And I thought, I'm going to get fired any day, because the drawings just fell apart. But I quickly realized, as I watched what the other artists did, that they were working from photography. They were projecting and tracing, whatever it took. And I thought, "I can't do that. I'm a purist, right?" I'm going to do it the “right way.” Quickly, I realized I was not going to be able to build those skills fast enough to keep up. It was going to take years, and I didn't have that time.

So, I promised myself, “All right, if I do this, I'm going to let it teach me how to draw better.” Turns out that is exactly what it did. And I still train my students to do that now, because it accelerates the learning curve, because you're actually following forms and foreshortening forms, and you're understanding foreground and middle ground and background by tracing that stuff. I learned that guys like Vermeer had used lensing and other similar projection methods.

My skills ramped up really fast, to the point where a couple of years later at the studio, I decided to go freelance. They really wanted me to stay. Some days I wish I had, because they were such an amazing group of people. We're still friends, most of us. We had the best leader, Gary Kelly, and he is one of the most-awarded American illustrators of all time and he's brilliant. It was a wonderful start to my career.

Q: You said that you were somewhat pushed away from oil painting, but frankly, I think that is the medium that most people know you for. What eventually drew you towards focusing on the medium, and how did it become your favorite?

I held on to my feeling and my dream of wanting to become like those painters I admired, and they happened to all be oil painters. A lot of new illustrators want to be great painters, but when they start they get knocked down, pushed and shoved. I think that what comes into play most is your stamina and how much you stick to it and dig in. At one point in my early career, I'd had enough. At the time, I had eight different techniques I was working with that were all selling. I had colored pencil, gouache, airbrush, regular pencil, charcoal and more. I was often being asked to emulate someone else’s style and eleven years in, I'd had enough. I thought, I'm going to paint for myself and if I fail, then I fail. Then I'll just go off and be a fighter pilot or something if it all falls apart. But the first thing I painted grabbed a lot of attention and pushed me to continue on.

That first piece was a play on Picnic on the Grass by Manet. It was a bunch of guys sitting around having coffee in a café, but there's a nude sitting at the table. That got a lot of attention. I learned that building curiosity is how you pull the audience in. And then I started to realize that illustrating is about the ideas just as much as the technique. The two have to marry. We see this now with AI. It's only going for the technique. It's not going for the idea. It has to pull from somewhere, and it's an amalgamation of something else.

Q: Being an illustrator that practices so many mediums, I’m curious with such a long spanning career, how you view the evolution of digital art and how that compares to more traditional and historical mediums?

I remember when I realized, ‘wait a minute, there's something happening with the computer scientists, and it is coming to the art world.’ There was one early depiction I saw of a toothpick through an olive in a martini glass that was created by a computer scientist who wasn’t an artist in the traditional sense. It was low-res, but it looked amazing. And I remember thinking, “Yeah, that's where it's headed.” So, I bought a computer in 1981.

I got my first Apple II Plus and I thought that maybe I was going to be a digital artist, or computer artist, as I thought of it then. The trouble was, at the time, the only way to learn how to use it was by reading a large stack of books that taught you the programs. It wasn’t intuitive at all. Every time I would input something, it would just say ‘syntax error.’ I kept working on it, and while I was trying to learn it, a traditional job would come in and I would take it to survive.

Then I’d go back to the computer, have all kinds of problems, and another job would come in and I'd go back to drawing. As this went on, the drawing became more interesting to me and I started to get better. The computer eventually got pushed into the corner and started to gather dust. At that point, I was committed to drawing. I didn’t think much about digital for a long time after that.

I painted like crazy all through the ‘80s. In the early ‘90s, National Geographic Magazine called and I was basically painting chunky oil paint at the time, which is not something they usually bought. They always bought the highly detailed stuff. But they loved what I was doing and we had a relationship for a long time working together. Then digital started to crawl into the field. At that point, I was against it and thought it really didn’t look good, no texture, no strokes. But then I watched as it got better. That was when I met Irene Gallo (at the time Art Director of Tor Books).

We would talk about this all the time. She would say, ‘I don't care what technique it is, as long as it works for the book cover. If they hit the deadline, what's the problem?’ That really changed my opinion and I started to listen to that.

So, I kept painting and I was pretty lucky. I could sell the look of the paint and people were buying it. Then I realized they were buying it because it was unique at that point. A lot of newer illustrators went into digital, but the kind of clever, smart techniques were drifting away from traditionally practiced mediums. Yet the oil paint was still there. And I was moving through it in different ways, using it with different approaches. As I got better and secured more jobs, I just laid my foot on the pedal.

Q: Do you ever play around with digital painting or is that something that you never picked back up?

Yeah. I love it, actually, it's very cool. Now I will often send rough work to a client that's done digitally so they get a sense of where I’m going, but then I do the final in oil.

Q: One of your crowning achievements was an original work of yours, Above the Timberline, in which you wrote and illustrated the story. What originally sparked this idea and how did it evolve into a fully realized story? I’ve heard legends about how many paintings you did in a single year for that publication. Can you tell us about the process?

I’ve had an interest in writing for many years and have written a lot, but my painting always took the lead. A film crew wanted to record a video of how I paint and I had to quickly put together an image. Adventure and mystery poured out and I found myself designing a character struggling on a snowy mountainside with his polar bear pack. It combined my love of hiking and survival with my interest and love for animals and mountains. I called it Above the Timberline and a friend encouraged me to show it to a publisher. I hadn’t thought to do that, but I gave it a shot and they were immediately curious. I then had to sit down and hash out why my character was on that mountainside. Five years later, I had something to work with and sold it to Simon & Schuster.

When the project first started, I was really excited, but then I realized that I needed to do 123 paintings in 11 months. They weren’t small either. I was working with paintings that were 15 inches tall by 47 inches wide. I love widescreen and horizontal paintings, so this was perfect. It was really fun and since I didn’t have deadlines within that time period, I could start a painting and sit on it for a little while, study it and try to determine what it needed before finishing.

One day, I might paint all ice and snow. Another day I'd paint just characters and another day airships or polar bears. I was able to piece them together going back and forth. And if I had the energy to go ahead and finish one, then I would do it, but it would still go on the wall, where I could study it and tweak it later on. I never had that luxury before, but for the most part, I had the final say on what the painting was going to be.

I was having a great time on my own and really didn’t have a formal art director. However, I had to stop all other work, other than teaching twice a week and finishing a couple of DVD covers for Eric Skillman at the Criterion Collection. I love those guys, so I slid those in there.

After the first three months, I punched out 49 paintings and I was a little bit toasty. So, I slowed down for a couple of weeks and then I picked my speed back up again and carried on through the summer. And in October (two months before the deadline), I had about 22 left to do and finished in time for them to be photographed as well. I had to clean all those up and get them in on the due date. The day I turned in the last painting to the photographer to scan, I thought, “my throat feels funny,” and boom—I was sick as a dog right after that. Stayed just fine the whole year painting and then I got sick. The adrenaline had kept me going.

Seven years after I painted that initial image, the book came out. I’d started the story with very small thumbnail sketches, drawing while daydreaming. This led to curiosities about the main character, which led to places he’d be, which led to conversations of dialogue, which led to an overall story. I basically started in the middle and worked my way outward. I had an ending in mind, and made small steps to connect the dots to get there. The biggest hurdle was trying to keep the story contained to 250 pages…and gathering enough reference to work from. Sometimes I just had to work from my head, but it eventually all got done.

Q: One iconic project that you worked on was a series of covers for the legendary Western Author Louis L’Amour. How did they find you for that project and what was the process like working with the L’Amour estate?

I originally got contacted by the Louis L'Amour Western Magazine to discuss working on covers for his novels. They saw some of my work in National Geographic and thought I could handle cowboys based on my previous illustrations. I did a few smaller jobs for the Magazine at first, but didn’t know they were looking for an artist shift on the covers. They wanted to get away from super-detailed realism and into more of an expressive painting style for the new covers.

They had been looking for someone for years and Beau L'Amour had seen my work in the magazine (He actually bought the first painting I did for it). He went to his contacts and said, ‘I think this is the guy.’ The first thing they wanted to do was a series of the Sackett family novels, which has 17 books in it. I thought, ‘I don't think I can read all of them and make the deadline.’ So, Beau and I would sit on the phone for hours, and he would tell me the stories and talk about what he wanted to see. Then I would take notes and start doing thumbnails. It got to the point where the art director would just say, ‘call Beau.’ I would send in a sketch to the art director that was already approved by him. I have now done close to 70 book covers for them and even have an exhibit of 50 of these at the A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art, in Trinidad, Colorado.

Q: You’ve done concept art and promotional work for film projects—how is that workflow different from your illustration background? Were there any film-related projects that pushed you outside your comfort zone stylistically or technically?

I’ve worked in several categories for films: movie posters (Dune ‘84, The River), original paintings for on set (Finding Forrester), paintings for illustrations within the film story (Buster Scruggs), concept work (Narnia), credits (Play Dirty), and DVD covers (a wide range for Criterion Collection). When directors come to me, they usually want something specific, something they’ve already visualized, since Hollywood productions aren’t crazy about experimenting with budgets. So, I end up pushing myself outside my range. Recently, I used a palette knife to smear paint around while recording the process of painting a couple of portraits for the titles of the film, Play Dirty.

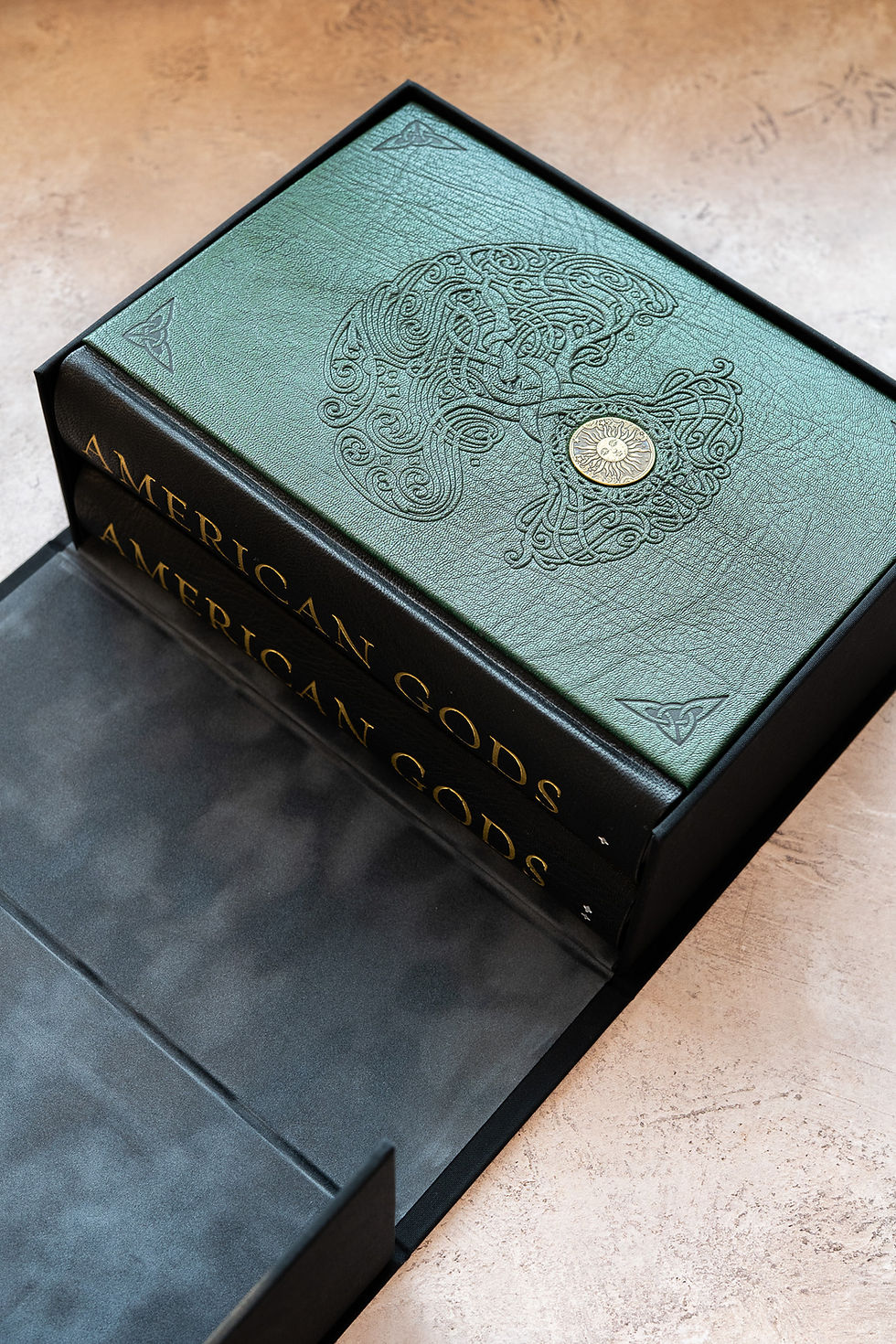

Q: Many of our readers are small/fine press book collectors and will recognize your work from the many illustrated books you have done with presses like Lyra’s Books, Arete Editions, Conversation Tree Press, Curious King, The Folio Society and Fablelistik. What do you appreciate about working in this space and what were some of your favorite projects? Why do you think you have been so frequently used in the modern fine press movement going on right now?

I love working in the limited edition press arena because the publishers come and ask me to give the story my personal vision. While I’m still working for the client, I’m given much more freedom to explore. I share that exploration with the client. We talk and work out the necessary imagery I’ve developed for them with an eye for the final edition and how it will feel to the collector. It’s a collaboration, and that’s always admirable. Recently I worked on a favorite edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz for Lyra's Books, and I finished paintings for The Legend of Sleepy Hollow in February which should be released soon.

I think in the business, it really does work out that if you establish a good working relationship with a client, word gets out you’re not going to stab them in the back. You’re going to meet the deadline and be great to work with. It's kind of like being the Tom Hanks of illustration. Everybody loves to work with him because he understands the problems that need solving and he moves with it and does the work.

Back in 2004 or so, Marcelo Anciano (current owner of Arete Editions) contacted me. He had asked around and was trying to find someone to do the painting for the third volume of books he was doing for a series of Conan stories. He emailed me, and said, “You come highly recommended as an oil painter, would you be interested in Conan?” I told him that I didn’t know anything about Conan and I was going to have to read up on it. We got along as fast friends and I would see him whenever I went to London. That relationship was something he remembered when we weren't working together. Many years later, he got into limited edition books and he called me up about The Picture of Dorian Gray. Initially, I said I would be interested, but the thing about The Picture of Dorian Gray is that everybody always paints the last painting in the story. I had this idea about watching the picture deteriorate over time, and he loved the idea. I did nine of them and the Oscar Wilde people heard about it and got on board and fell in love with the idea as well.

While I was working with Marcelo, he had his books produced through Rich Tong, who runs Lyra’s Books. The three of us got talking and they asked me what books I would like to do if I could pick anything. I sent him a list of ideas and they were very interested in the Wizard of Oz, so I was immediately on board. As a kid I used to watch that in black and white TV in my living room with my parents every spring and so I knew the movie inside and out, but I didn't really know the books that well. They’d call and we would discuss aspects of each production and everybody seemed really great in the small press business. They're all just people who love publishing and I've always loved books so it’s a great fit.

Q: As your career has evolved, do you find yourself trying to focus more on specific areas of illustration, or are you still open to new and interesting projects that are outside of what you are most known for?

It has certainly narrowed down at this point of my career, mainly publishing and some easel work. I would love to simply work on the books I want to work on and sell the originals in galleries, and become the gallery painter I've always pictured myself becoming. However, every now and then, a special job comes up. I just finished doing 11 murals for a museum in Texas on the early developing days of the state and how it all started. I’ve also done some postage stamps and those are awfully fun.

Recently, I’ve been doing mission patches for NASA astronauts and that's also been a great experience. It's something you'd think would be simple, but they need everything perfect. I’d spend a year or so going back and forth, but sitting down with astronauts at NASA—it’s just too doggone cool. I recently finished the mission patch for the Artemis 2 crew that's going to circle the moon and come back. I had to design two patches, but I’ll let the astronauts reveal why.

I'm hoping to do more gallery work in the future, primarily through Galerie Daniel Maghen in Paris. They approached me at San Diego Comic Con and initially I didn’t think much of it, but they kept reaching out to me and at some point I spoke to Charles Vess about it and he spoke very highly of them. He said, “If they want you to do a show, do it.” I started talking to Olivier from the gallery and they did a show for me that was just wonderful. I was supposed to do another show with them, and then the pandemic struck and everything went to hell. So that's kind of the next thing I want to do.

Q: Throughout your long and illustrious career, what are the things that have changed the most about your industry and what has remained most consistent?

The work has changed, the styles and interests have changed, and the process of getting work and having steady clients has changed. The people haven’t changed much, though. Deadlines are shorter, and productions are smaller, but the people are all trying to do their best to create a solid visual together. The teamwork is still a remarkable and wonderful aspect when it works well, and it’s still the same kind of failure of attitudes when it doesn’t. So, I try to instill in the students that I mentor that learning to work with people will get them very far, even when the practicalities of the workflow shifts and changes. Roll with the changes, take your risks, and be professional about surviving in the arts.

Q: What are you currently working on and is there anything you can share about upcoming projects in 2025 and 2026?

I’m about to start working on several more limited edition books, Frankenstein and A Christmas Carol, plus the third volume of the Foundation series for Conversation Tree Press and the third volume of The First Law series, by Joe Abercrombie, with Curious King. I plan to have an art book of many of my paintings come out in 2026, and another based on my posts for the Muddy Colors website. I’m working on releasing a folio of many of my paintings from some of the limited editions, and hoping to release a book of sketches eventually as well.

This interview was done in a series of communications back and forth and a Zoom call and we want to thank Greg for his willingness to be a part of this series and also for collaborating with us on a future broadside. If you want to check out some of Greg's many past works, you can take a look at his portfolio on his website https://www.manchess.com/ To stay up to date on the breadth of everything he is working on, you can follow him on Instagram.

Interview by: Zach Harney of the Collectible Book Vault

Congrats to our winner of the broadside giveaway Suzy Araiza!

Love reading this Q&A’s. Can’t wait for CK’s LAOK!

Great interview. Love to read about how he got started to get to where he is today.

Any book with Manchess art in it immediately gains added value. Great interview as always!

Wonderful interview